Free variables and bound variables

In mathematics, and in other disciplines involving formal languages, including mathematical logic and computer science, a free variable is a notation that specifies places in an expression where substitution may take place. The idea is related to a placeholder (a symbol that will later be replaced by some literal string), or a wildcard character that stands for an unspecified symbol.

The variable x becomes a bound variable, for example, when we write

- 'For all x, (x + 1)2 = x2 + 2x + 1.'

or

- 'There exists x such that x2 = 2.'

In either of these propositions, it does not matter logically whether we use x or some other letter. However, it could be confusing to use the same letter again elsewhere in some compound proposition. That is, free variables become bound, and then in a sense retire from being available as stand-in values for other values in the creation of formulae.

In computer programming, a free variable is a variable referred to in a function that is not a local variable or an argument of that function.[1] An upvalue is a free variable that has been bound (closed over) with a closure. Note that variable "freeness" only applies in lexical scoping: there is no distinction, and hence no closures, when using dynamic scope.

The term "dummy variable" is also sometimes used for a bound variable (more often in general mathematics than in computer science), but that use creates an ambiguity with the definition of dummy variables in regression analysis.

Contents |

Examples

Before stating a precise definition of free variable and bound variable, the following are some examples that perhaps make these two concepts clearer than the definition would:

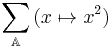

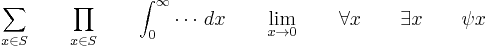

In the expression

n is a free variable and k is a bound variable; consequently the value of this expression depends on the value of n, but there is nothing called k on which it could depend.

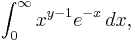

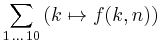

In the expression

y is a free variable and x is a bound variable; consequently the value of this expression depends on the value of y, but there is nothing called x on which it could depend.

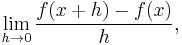

In the expression

x is a free variable and h is a bound variable; consequently the value of this expression depends on the value of x, but there is nothing called h on which it could depend.

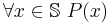

In the expression

z is a free variable and x and y are bound variables; consequently the logical value of this expression depends on the value of z, but there is nothing called x or y on which it could depend.

Variable-binding operators

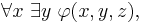

The following

are variable-binding operators. Each of them binds the variable x.

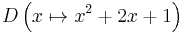

Note that many of these are operators which act on functions of the bound variable. In more complicated contexts, such notations can become awkward and confusing. It can be useful to switch to notations which make the binding explicit, such as

for sums or

for differentiation.

Formal explanation

Variable-binding mechanisms occur in different contexts in mathematics, logic and computer science. In all cases, however, they are purely syntactic properties of expressions and variables in them. For this section we can summarize syntax by identifying an expression with a tree whose leaf nodes are variables, constants, function constants or predicate constants and whose non-leaf nodes are logical operators. This expression can then be determined by doing an inorder traversal of the tree. Variable-binding operators are logical operators that occur in almost every formal language. Indeed languages which do not have them are either extremely inexpressive or extremely difficult to use. A binding operator Q takes two arguments: a variable v and an expression P, and when applied to its arguments produces a new expression Q(v, P). The meaning of binding operators is supplied by the semantics of the language and does not concern us here.

Variable binding relates three things: a variable v, a location a for that variable in an expression and a non-leaf node n of the form Q(v, P). Note: we define a location in an expression as a leaf node in the syntax tree. Variable binding occurs when that location is below the node n.

In the lambda calculus, x is a bound variable in the term M = λ x . T, and a free variable of T. We say x is bound in M and free in T. If T contains a subterm λ x . U then x is rebound in this term. This nested, inner binding of x is said to "shadow" the outer binding. Occurrences of x in U are free occurrences of the new x.

Variables bound at the top level of a program are technically free variables within the terms to which they are bound but are often treated specially because they can be compiled as fixed addresses. Similarly, an identifier bound to a recursive function is also technically a free variable within its own body but is treated specially.

A closed term is one containing no free variables.

Function expressions

To give an example from mathematics, consider an expression which defines a function

where t is an expression. t may contain some, all or none of the x1, ..., xn and it may contain other variables. In this case we say that function definition binds the variables x1, ..., xn.

In this manner, function definition expressions of the kind shown above can be thought of as the variable binding operator, analogous to the lambda expressions of lambda calculus. Other binding operators, like the summation sign, can be thought of as higher-order functions applying to a function. So, for example, the expression

could be treated as a notation for

where  is an operator with two parameters—a one-parameter function, and a set to evaluate that function over. The other operators listed above can be expressed in similar ways; for example, the universal quantifier

is an operator with two parameters—a one-parameter function, and a set to evaluate that function over. The other operators listed above can be expressed in similar ways; for example, the universal quantifier  can be thought of as an operator that evaluates to the logical conjunction of the boolean-valued function P applied over the (possibly infinite) set S.

can be thought of as an operator that evaluates to the logical conjunction of the boolean-valued function P applied over the (possibly infinite) set S.

Natural language

When analyzed in formal semantics, natural languages can be seen to have free and bound variables. In English, personal pronouns like he, she, they, etc. can act as free variables.

- Lisa found her book.

In the sentence above, the possessive her is a free variable. It may refer to the previously mentioned Lisa or to any other female. In other words, her book could be referring to Lisa's book (an instance of coreference) or to a book that belongs to a different female (e.g. Jane's book). Whoever the referent of her is can be established according the situational (i.e. pragmatic) context. The identity of the referent can be shown using coindexing subscripts where i indicates one referent and j indicates a second referent (different from i). Thus, the sentence Lisa found her book has the following interpretations:

- Lisai found heri book. (interpretation #1: her = Lisa)

- Lisai found herj book. (interpretation #2: her = female that is not Lisa)

The distinction is not purely of academic interest, as some languages do actually have different forms for heri and herj: for example, Norwegian translates heri as sin and herj as hennes.

However, reflexive pronouns, such as himself, herself, themselves, etc., and reciprocal pronouns, such as each other, act as bound variables. In a sentence like the following:

- Jane hurt herself.

the reflexive herself can only refer to the previously mentioned antecedent Jane. It can never refer to a different female person. In other words, the person being hurt yesterday and the person doing the hurting are both the same person, i.e. Jane. The semantics of this sentence is abstractly: JANE hurt JANE. And it cannot be the case that this sentence could mean JANE hurt LISA. The reflexive herself must refer and can only refer to the previously mentioned Jane. In this sense, the variable herself is bound to the noun Jane that occurs in subject position. Indicating the coindexation, the first interpretation with Jane and herself coindexed is permissible, but the other interpretation where they are not coindexed is ungrammatical (the ungrammatical interpretation is indicated with an asterisk):

- Janei hurt herselfi. (interpretation #1: herself = Jane)

- *Janei hurt herselfj. (interpretation #2: herself = a female that is not Jane)

Note that the coreference binding can be represented using a lambda expression as mentioned in the previous Formal explanation section. The sentence with the reflexive could be represented as

- ((λx(x hurt x))(Jane))

Pronouns can also behave in a different way. In the sentence below

- Ashley met her.

the pronoun her can only refer to a female that is not Ashley. This means that it can never have a reflexive meaning equivalent to Ashley met herself. The grammatical and ungrammatical interpretations are:

- *Ashleyi met heri. (interpretation #1: her = Ashley)

- Ashleyi met herj. (interpretation #2: her = a female that is not Ashley)

The first interpretation is impossible, but the second interpretation is grammatical (and in this case, is the only interpretation).

Thus, it can be seen that reflexives and reciprocals are bound variables (known technically as anaphors) while true pronouns can be free variables in some grammatical structures or variables that cannot be bound in other grammatical structures.

The binding phenomena found in natural languages was particularly important to the syntactic government and binding theory (see also: Binding (linguistics)).

See also

References

A small part of this article was originally based on material from the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing and is used with permission under the GFDL. Most of what now appears here is the result of later editing.

![f = \left[ (x_1, \ldots , x_n) \mapsto \operatorname{t} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1bd950955e564584c597ae6323867163.png)